Unpacking the Investment Opportunities in the Changing Asian Supply Chain

As the fulcrum of economic strength moves persistently towards Asia and geopolitical climate shifts are ever more turbulent, the issue of supply chain transformation is often front of mind. It is easy to believe the simplistic popular narrative of supply chain moving back home away from Asia. The reality is much more nuanced but is still extremely positive for most Asian economies. It pays to understand what is happening in order to profit from an investment perspective.

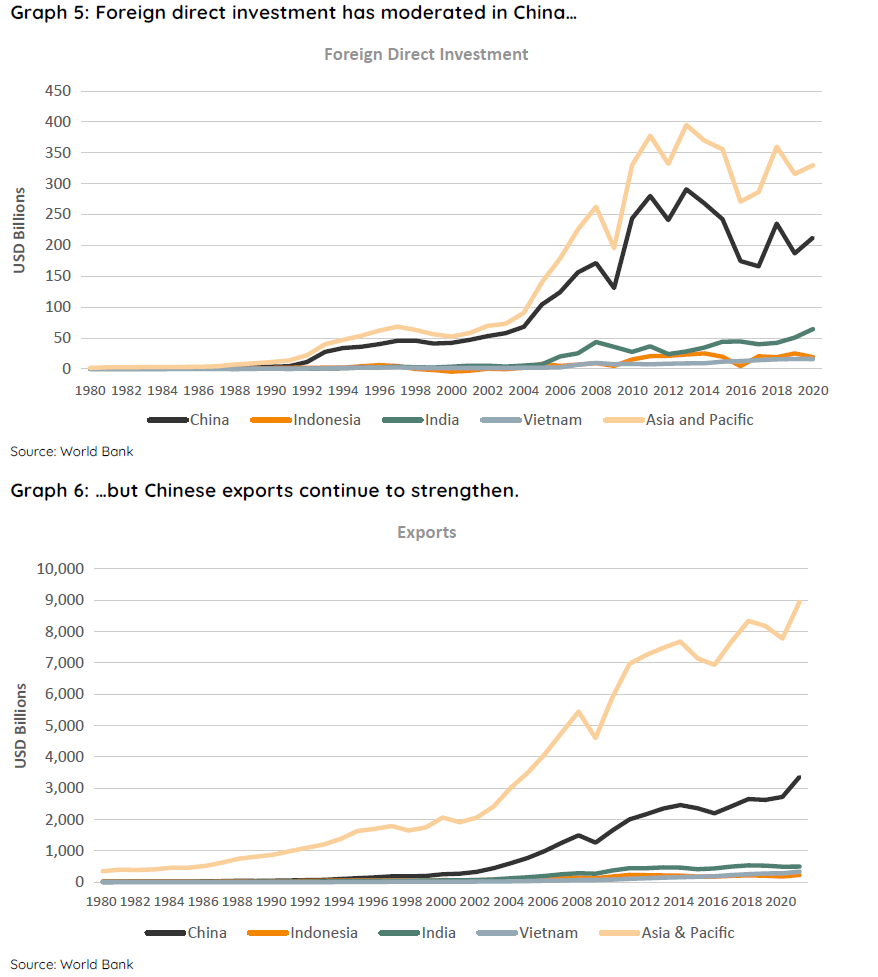

China is still the manufacturing powerhouse for the world, but when it comes to incremental capacity addition to supply the developed world, it is missing out on the margin. The economics of rising labour and environmental costs in China dictates the decision making of manufacturers and exporters, with incremental dollars invested to building factories moving from China to other Asian countries.

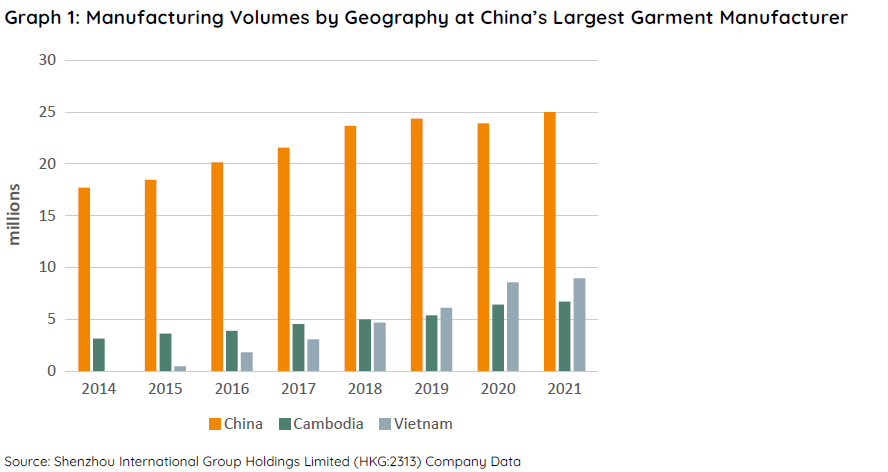

Manufacturers supplying the huge and growing Chinese market and global brands are growing capacity in both China and in Cambodia and Vietnam. Whilst factories supplying the Chinese market are not going to move out of China, Chinese companies with growing export businesses are increasingly moving this manufacturing capacity to neighbouring countries. For example, Yue Yuen (a major outsourced manufacturer of sportswear apparels such as Nike, Adidas, and Li Ning) has been building factories in Cambodia and Vietnam in recent years, following the lead of China’s largest garment manufacturer, Shenzhou.

Global suppliers of the less labour-intensive industries like tyres and car parts manufacturing are also moving their factories to South-East Asia and Eastern Europe to take advantage of the lower costs. To effectively reduce the cost of production, Chinese nickel companies are closing their domestic operations and investing in countries such as Indonesia to supply the voracious appetite for electric vehicles.

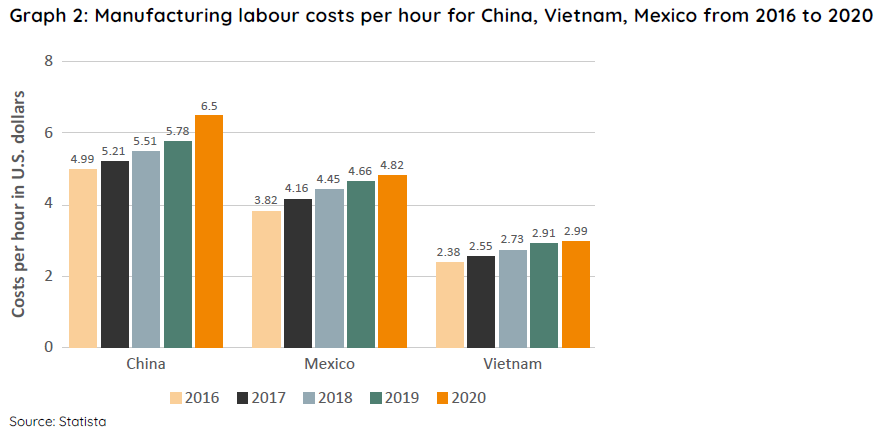

Vietnam and other South East Asian countries are benefiting immensely from this dynamic. The shift in supply chains has been taking place for more than a decade, and it is not a recent phenomenon driven purely by worsening geopolitics or COVID. It was primarily driven by the rising labour costs in China.

Gone are the days when Chinese labour was cheap and plentiful, when migrant workers moved into the cities in the tens of millions, earning wages of USD200-300 a month. The supply of cheap migrant workers has been in decline for over a decade, and wages have gone up significantly with breathtaking economic development. Factory owners, many of whom are Chinese and Taiwanese, moved part of their operations to ASEAN countries that offer an abundance of cheap labour. Asian Governments could see the opportunity and steadfastly improved quality of their institutions and infrastructure like ports, power and roads. The aspirational young population in these countries could envisage what they can achieve and are electing pro-development governments, making this a persistent trend.

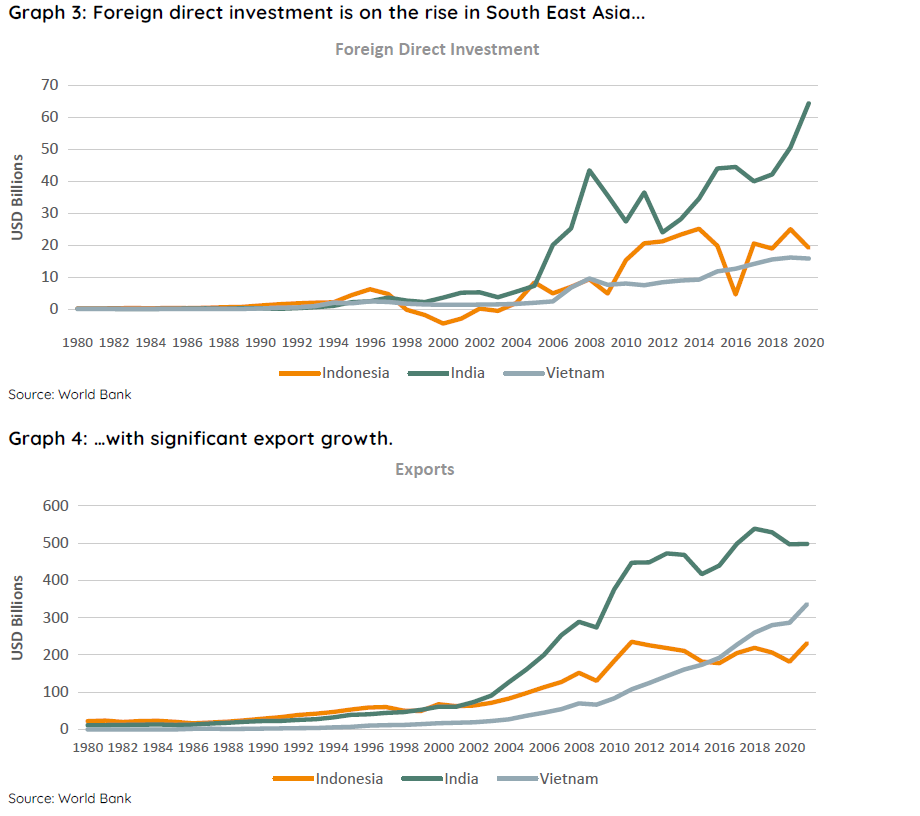

It is a rather exciting time for these Asian economies, chiefly Vietnam, Indonesia and to some extent India. Significant foreign direct investments are flowing into these countries thanks to relocation dynamics. Economic growth is straightforward, resembling that of China two decades ago, steadily transforming Asian economies into low-to-mid end manufacturing hubs for the world! Export performance out of these countries, in particular Vietnam, has been nothing short of breathtaking in recent years.

While the supply chain diversification trend is real, the huge domestic consumption market is keeping factories in China to best serve the local customers. The Chinese economy is second only to that of the US in size and is growing at a faster clip. Why leave this prospective market?

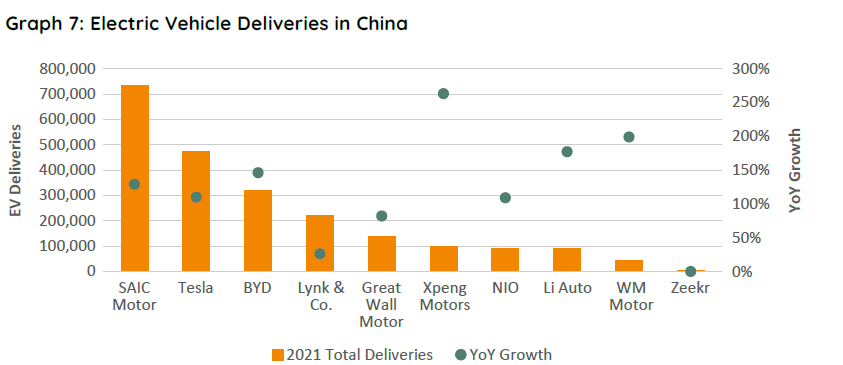

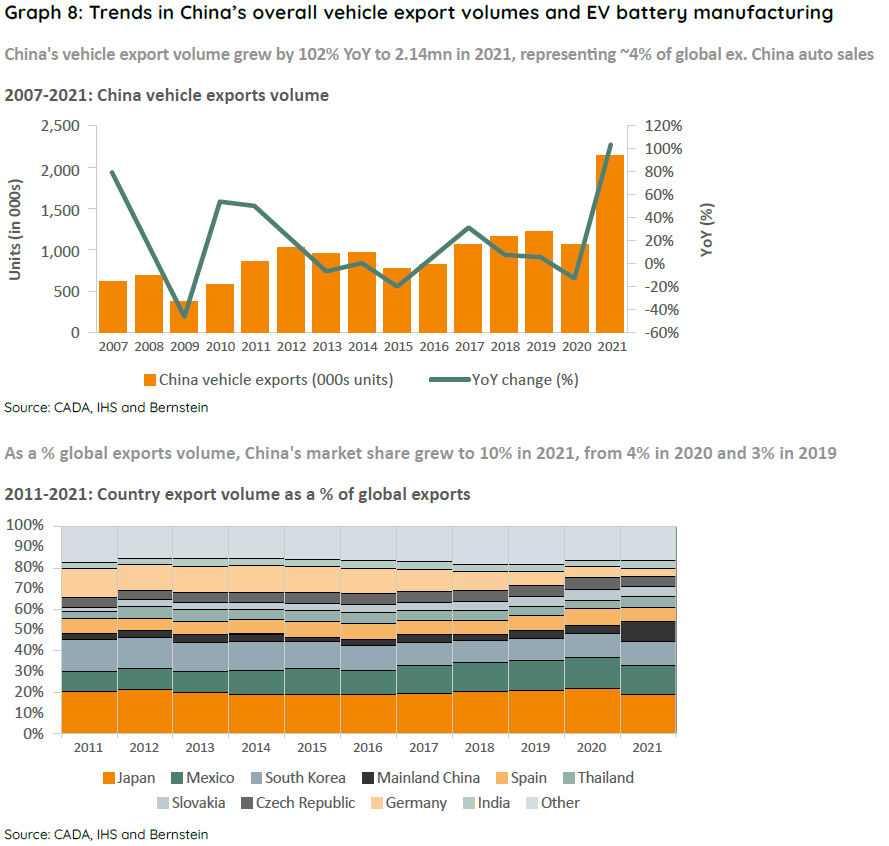

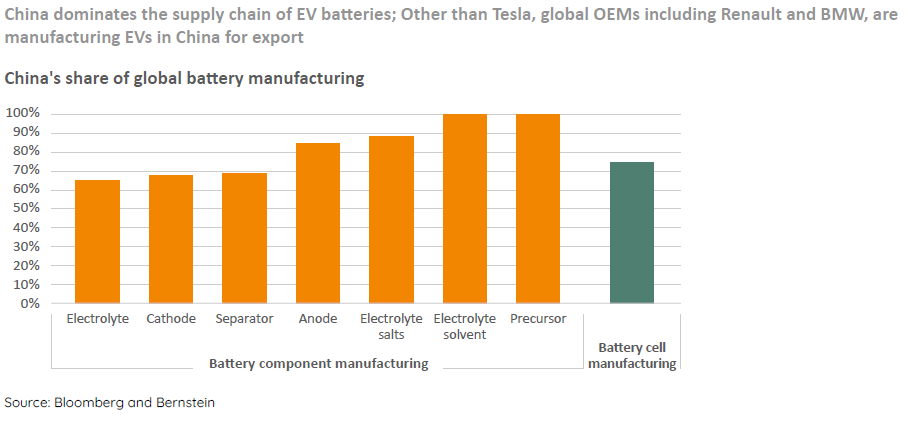

The reality is also that manufacturing of low-end textiles, footwear and toys is not China’s main game anymore as the country’s labour costs have climbed. It is fast marching towards into manufacturing products with a higher technological content. For example, Sany Heavy has become the world’s biggest manufacturer of excavators, a product that was previously dominated by Caterpillar of the US and Komatsu of Japan. Exports of Sany’s excavators doubled in 2021. Another example is the car industry. Quietly, China is turning into an automobile powerhouse, doubling auto exports in 2021. When it comes to batteries – and therefore electric vehicles – China also dominates.

The story for China has changed from simply dominating thanks to low labour costs manufacturing low-end goods for the world, to one that is rapidly enhancing its technological capability.

The Asian economic miracle is alive and well. Given the changing dynamics however, from an investment perspective, our focus at Ox Capital has to be differentiated. We are focussed on strong Chinese companies with the technological expertise that will enable them to grow as the country continues to climb the technological ladder. The new Asian Tigers of Vietnam, Indonesia and India are grasping the opportunity to become the factories of the world, reminiscent of the Chinese development story 20 years ago.

The economic development in Asia appears to be unstoppable, fuelled by rapid productivity improvements, rising living standards and improving technological knowhow. Vast opportunities are on offer and valuations are at significant discount to that of developed markets.

At Ox Capital, we focus on strong businesses in the rapidly growing parts of the world while protecting downside during volatile times. The future is bright in Asian markets!

This material has been prepared by Ox Capital Management Pty Ltd (ABN 60 648 887 914 AFSL 533828) (OxCap). It is general information only and is not intended to provide you with financial advice or take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Any projections are based on assumptions which we believe are reasonable but are subject to change and should not be relied upon. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Neither any particular rate of return nor capital invested are guaranteed.